“In order to enter that process of this individual psychological and algorithmic confirmation, you do need to have some extent of susceptibility to some sort of narratives from the left or the right,” Wojcieszak says. “If there are some social or political issues in which you have some views, that can start the process.”

You can imagine someone who isn’t particularly politically extreme but does harbor certain fears about ways the country is changing being pulled in by extremists and becoming extreme themselves as they get increasingly embedded in that community. People need community, and extremists can give them that. They’ll be welcomed by this community, Wojcieszak says, and they’ll feel the psychological need to start going along with whatever that community’s narrative is on any number of issues.

Mike Gruszczynski, an assistant professor of communication science at Indiana University, says a distrust in institutions, such as news media and the government, can lead to people creating echo chambers and often falling for disinformation because it appeals to their political beliefs. He says this has been found to be more common on the political right than the political left.

“You have a lot of people on the right wing of the political spectrum who have been highly distrustful of traditional journalism for quite a while,” Gruszczynski says. “Not only are they distrustful of it, but they exist in a kind of feedback loop where their chosen leaders tell them that the things that come out of the media are false or biased.”

One of the ways society can help prevent people from going down these rabbit holes and becoming more extreme is by teaching them media literacy. Gruszczynski says it won’t necessarily be easy to do, especially because there’s so much disinformation out there and it’s often quite convincing. But it’d be worth the effort. “Everyone kind of has to be their own detective in a way now,” Gruszczynski says.

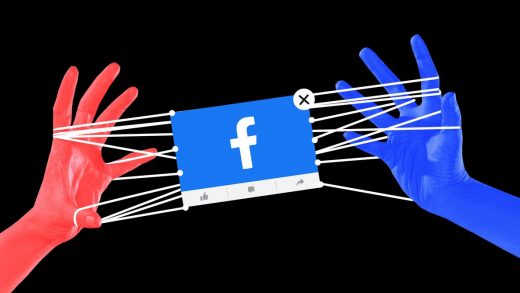

It often feels like an insurmountable challenge, Wojcieszak says, because those who have become politically extreme are living in such a different reality than the rest of the populace. If someone is spending most of their time on extremist forums or in extreme groups on social media, for example, it’s hard to reach them and bring them back to reality. She says improving social media algorithms so these platforms are less likely to make people more extreme in the first place could be a good place to start when it comes to attacking this problem.

“In the US, things have gotten so deeply bad for some groups. The people who are, say, true Trump believers or who are convinced Covid was a hoax—I’m not sure if you can deprogram them,” Wojcieszak says.

Society may not be able to pull everyone out of these rabbit holes, but increased media literacy and social media platforms that aren’t designed to confirm people’s existing beliefs and make them more extreme could help fewer people become radicalized. It’s a widespread problem that will take time to address, but the status quo does not seem sustainable.